Author: Rob Gowland

The October Revolution took place in the second decade of the last century. In other words, it was a long time ago: so why should we be concerned with it in the 21st century? That’s easy: because the change it heralded in the way society operates was so profound and so far-reaching that it continues to influence or even determine international relations and the aspirations of the world’s people today.

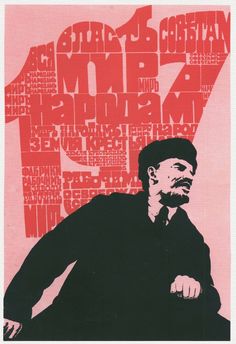

Its most significant aspect was that it was a Red revolution: for the first time in history, the working class successfully overthrew the rule of the bourgeoisie and took control of society themselves. There was a world war raging at the time, the most wide-ranging ever known, which had earned itself the name “the Great War”. To the shock of the leaders of capitalism everywhere, the revolutionary government of Russia proposed that all the belligerents in this glorious event should end the bloodshed and cease hostilities.

This radical proposal outraged the rest of the world’s governments. Most of them were using the War, in one way or another, to acquire the territory of other countries, to win control of global markets, or to militarily dominate vast sectors of the globe for their own financial benefit. So they decided to invade the country that had spawned these upstart “Reds” and get rid of them.

Fourteen countries, including all the “Great Powers,” invaded impoverished Soviet Russia. However, the Reds fought tenaciously to defend their Revolution and they were supported by the world’s workers: soldiers sent to fight in Russia threatened to mutiny, colonial peoples threatened to rebel and trade unions in developed capitalist countries threatened strike action. At the same time, Red Revolution broke out in other imperialist states: the German Kaiser was tossed out and surrendered his sword to a startled Dutch border guard.

The Austro-Hungarian emperor was similarly given his marching orders and a Soviet republic was set up in Hungary instead. The Ottoman Empire also collapsed and a bourgeois-democratic regime was established in a new, albeit much smaller, Turkey. To the dismay of capitalism, this new bourgeois Turkey sought friendly relations with its neighbour, Soviet Russia.

For the time being, capitalism had to admit defeat. However, by the end of the 1920s they were again ready to invade the USSR, the centre of the “contagion” of Revolution. The plan only collapsed when the capitalist system itself fell in a heap, the result of an economic disaster called “The Great Depression”. Significantly, the only country not affected by the Depression was the USSR. Once again, the capitalist powers were thwarted of their prey.

Terrified that the Depression would lead the disaffected workers to once again resort to Red Revolution, capitalist corporations turned to fascism to protect their interests. Hungary and Italy had already gone fascist in the 1920s. By the end of the decade, with their economies in tatters and millions out of work, numerous countries in the rest of the world saw their capitalists fund right-wing extremists who promised to use force if necessary to prevent the dreaded Reds from winning power.

Well-funded by corporate interests, support for fascism grew apace, notably in Portugal, Spain, France, Poland, Sweden, Norway, and the USA, as well as others including Britain and Australia. We even had our own fascist stormtroopers, here in Australia, the New Guard. Then as now, fascism fed on a mix of racism, crude nationalism, disillusion with bourgeois democracy and economic despair.

However, as the slogan of the time said with devastating accuracy, “Fascism means war!” Even those capitalist governments that had not gone fascist still thought they could use fascist regimes to achieve their own strategic ends. And the end ardently desired by most capitalists was the eradication of the fount of revolution, the Soviet Union. But the Soviet leadership skilfully deflected all the attempts to involve it in war, first with Japan (1935), then with Germany (1938).

Even after Britain and France had been obliged to declare war on Germany, the British ruling class tried to convince its population to support a war with Soviet Russia (1940) but by then there were few who didn’t recognise fascist Germany as the real threat. Certainly, the Soviet government knew that war could not be deflected indefinitely. However, by the time it came the USSR had had an invaluable breathing space, which it used to build up its defence capacity. Although the USSR was invaded by ten times the number of German divisions that were giving the British such a hard time in North Africa, the Soviet army was able to not only slow down the rate of the invaders’ advance but eventually to turn the tide, repulse the invaders and chase them all the way back to Berlin.

Ultimately, the war that was supposed to see the destruction of the home of revolution, the USSR, instead saw it not only victorious over fascism, but able to oversee the victory of Red Revolution throughout Eastern Europe and to actively assist its victory in China, and later to assist its first implementation in the Americas.

It was the ideas unleashed by the October Revolution that underlay the defeat of fascism in WW2 and then the global post-war surge in the national-liberation movement among the world’s colonial peoples. At the same time, workers in capitalist countries were able to gain concessions from a ruling class anxious to keep them sufficiently “contented” that they would not turn to the Socialist system that had emerged as a global rival to capitalism.

The defeat of Hitlerite Germany at the hands of an anti-fascist alliance that included not only capitalist powers but also the Socialist USSR, raised such expectations among the world’s people that henceforth the imperialists had to invent excuses for the use of force where previously they could virtually do as they pleased. The United Nations was set up with the express purpose of preventing wars.

The corporations that dominate capitalism were still determined however to eradicate the “scourge” of revolution from any country where the people might be inclined to want to enjoy the fruits of their own labour, or to prevent their country being embroiled in a war for corporate profit, or where the people might simply want to end exploitation by foreign corporations. The leaders of the capitalist world launched an ideological counter-attack they euphemistically called the “Cold War”, implying that it was less dangerous than regular “hot” wars. By expending an enormous amount of money that could have gone to serving people’s needs and employing an army of agents, agitators and propagandists, and all the resources of the bourgeois media, they sought to convince workers everywhere that capitalism was the only viable social system, that the Socialist countries were embarrassing failures that wanted to destroy them, and that consequently all money spent on war preparations, no matter how much, was money well spent.

By skilfully exploiting the ideological deficiencies that developed in the USSR during the leadership of Brezhnev onwards, capitalism pulled off its greatest coup: the overthrow of Socialism in the country where Red Revolution had first been successful.

The leaders of the imperialist powers rejoiced, but their victory proved dishearteningly elusive. The socialist genie that the Russian workers and peasants had released cannot be put back in the bottle. In Britain, the USA and parts of Europe, social democrats have found it advantageous in winning mass support to campaign loudly and openly (for the first time in decades) as Socialists. Workers in developed capitalist countries, who had been gulled into letting their unions decay or even disappear, are rediscovering the need for militant organising. And they are rediscovering that the only effective way to deal with the contradictions between those who create the wealth (workers) and the bosses who appropriate it for their own benefit is to withhold their labour by taking strike action in defence of their rights.

Employer-dominated governments have passed increasingly harsh laws to prevent industrial action by workers, and even to prevent workers organising at all.

Anti-union propaganda has been stepped up to an unprecedented degree, strikes outlawed in numerous countries, progressives belittled and extreme right-wing politicians encouraged. Fascist politicians and political parties are springing up like mushrooms after rain. However, life itself is daily demonstrating to workers the fundamental truths that the Revolutionary workers and peasants of Russia recognised in the freezing winter of 1917: that capitalists regard them as disposable fodder, commodities that can be thrown away when they have served their purpose – and their purpose is to make profits for capitalists. But those ragged, shivering, half-starved Russian workers and peasants also demonstrated something else, something profound: that the world’s workers and peasants can successfully run society, and run it for the benefit of all the people who actually create the goods and services that make up the real wealth of a society.

That is the legacy of the October Revolution, a guiding light for all people striving for a better life, a life based on principles of humanity, free from the lies and distortions of capitalism.

Long live Red October!