by Ruy Mauro Marini

Below we present Jorge M’s English translation of Ruy Mauro Marini’s Dialectics of Dependency, an important work in Latin American Marxism and overall theories of imperialism. Also included is a Postscript by Marini reflecting on the work and its arguments.

In their analysis of Latin American dependency, Marxist researchers have generally incurred in two types of deviations: the substitution of the concrete fact by the abstract concept, or the adulteration of the concept in the name of a reality rebellious to accept it in its pure formulation. In the first case, the result has been the so-called orthodox Marxist studies, in which the dynamics of the processes studied are poured into a formalization that is incapable of reconstructing them at the level of exposition, and in which the relationship between the concrete and the abstract is broken, to give rise to empirical descriptions that run parallel to the theoretical discourse, without merging with it; this has occurred, above all, in the field of economic history. The second type of deviation has been more frequent in the field of sociology, where, faced with the difficulty of adapting to a reality categories that have not been specifically designed for it, scholars with a Marxist background simultaneously resort to other methodological and theoretical approaches; the necessary consequence of this procedure is eclecticism, a lack of conceptual and methodological rigor, and a pretended enrichment of Marxism, which rather is its negation.

These deviations stem from a real difficulty: faced with the parameter of the pure capitalist mode of production, the Latin American economy presents peculiarities, sometimes as insufficiencies and sometimes – not always easily distinguishable from the former – as deformations. The recurrence in Latin American studies of the notion of “pre-capitalism” is, therefore, no accident. What should be said is that, even if it is really a question of an insufficient development of capitalist relations, this notion refers to aspects of a reality which, because of its overall structure and functioning, will never be able to develop in the same way as the so-called advanced capitalist economies have developed. This is why, rather than a pre-capitalism, what we have is a sui generis capitalism that only makes sense if we contemplate it in the perspective of the system as a whole, both nationally and, mainly, internationally.

This is true above all when we refer to modern Latin American industrial capitalism, as it has taken shape in the last two decades. But, in its most general aspect, the proposition is also valid for the immediately preceding period and even for the stage of the export economy. It is obvious that, in the latter case, insufficiency still prevails over distortion, but if we want to understand how one became the other, it is in the light of the latter that we must study the former. In other words, it is the knowledge of the particular form that Latin American dependent capitalism ended up taking that illuminates the study of its gestation and allows us to analytically understand the tendencies that led to this result.

But here, as always, the truth has a double meaning: if it is true that the study of the most developed social forms sheds light on the most embryonic forms (or, to put it with Marx, “human anatomy contains a key to the anatomy of the ape”)1, it is also true that the insufficient development of a society, by highlighting a simple element, makes its more complex form, which integrates and subordinates that element, more comprehensible. As Marx points out:

[…] the simpler category expresses relations predominating in an immature entity or subordinate relations in a more advanced entity; relations which already existed historically before the entity had developed the aspects expressed in a more concrete category. The procedure of abstract reasoning which advances from the simplest to more complex concepts to that extent conforms to actual historical development.2

In identifying these elements, Marxist categories must therefore be applied to reality as instruments of analysis and anticipations of its further development. On the other hand, these categories cannot replace or mix up the phenomena to which they are applied; that is why the analysis has to weigh them without this implying, in any case, breaking with the thread of Marxist reasoning, grafting onto it bodies that are foreign to it and that cannot, therefore, be assimilated by it. Conceptual and methodological rigor: this is what Marxist orthodoxy ultimately boils down to. Any limitation to the process of investigation that derives from it has nothing to do with orthodoxy, but only with dogmatism.

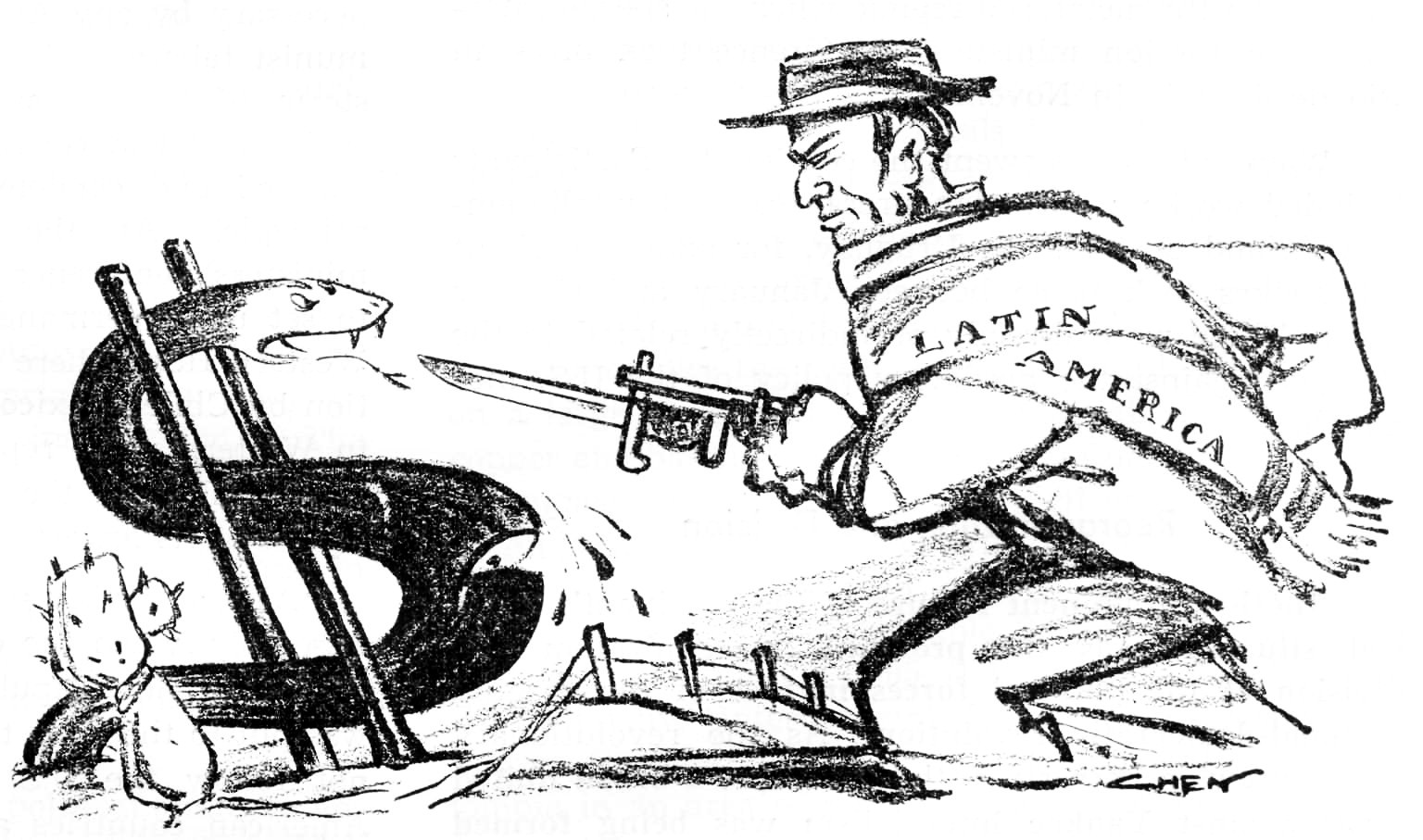

1) Integration into the world market

Forged in the heat of the commercial expansion promoted in the 16th century by emerging capitalism, Latin America developed in close consonance with the dynamics of international capital. As a colony producing precious metals and exotic goods, it initially contributed to the increase in the flow of merchandise and the expansion of means of payment, which, while permitting the development of commercial and banking capital in Europe, underpinned the European manufacturing system and paved the way for the creation of large-scale industry. The industrial revolution which started up this industry, corresponds in Latin America to the political independence gained in the first decades of the 19th century that gave rise, on the basis of the demographic and administrative fabric woven during the colonial period, to a group of countries that will gravitate around England. The flows of merchandise and, later, of capital, had their point of connection in England: ignoring each other, the new countries would link up directly with the English metropolis and, according to the latter’s requirements, would begin to produce and export primary goods in exchange for consumer manufactures and – when exports exceeded imports – debts.3

It is from this moment on that Latin America’s relations with the European capitalist centers are inserted into a defined structure: the international division of labor, which will determine the course of the region’s subsequent development. In other words, it is from then on that dependence takes shape, understood as a relationship of subordination between formally independent nations, in the framework of which the relations of production of the subordinate nations are modified or recreated to ensure the expanded reproduction of dependence. The fruit of dependence can therefore only be more dependence, and its elimination necessarily presupposes the suppression of the relations of production involved. In this sense, Andre Gunder Frank’s well-known formula on the “development of underdevelopment” is impeccable, as are the political conclusions to which it leads.4 The criticisms that have been made of it often represent a step backward in this formulation, in the name of precisions that claim to be theoretical, but which tend to go no further than semantics.

However, and therein lies the real weakness of Frank’s work, the colonial situation is not the same as the situation of dependency. Although there is continuity between the two, they are not homogeneous; as Canguilhem rightly says, “the progressive character of an event does not exclude the originality of the event”.5 The difficulty of theoretical analysis lies precisely in grasping that originality and, above all, in discerning the moment at which originality implies a change of quality. As far as Latin America’s international relations are concerned, if, as we have pointed out, it played a relevant role in the formation of the capitalist world economy (mainly by its production of precious metals in the 16th and 17th centuries, but especially in the 18th century, thanks to the coincidence between the discovery of Brazilian gold and the English manufacturing boom)6, only during the course of the 19th century, and specifically after 1840, did its articulation with the world economy become fully realized.7 This can be explained if we consider that it is only with the emergence of big industry that the international division of labor is established on solid foundations.8

The creation of modern large-scale industry would have been severely hampered if it had not relied on the dependent countries, and would have had to be carried out on a strictly national basis. In fact, industrial development presupposes a great availability of agricultural goods, which allows the specialization of part of society in specifically industrial activity.9 In the case of European industrialization, recourse to simple domestic agricultural production would have slowed down the extreme productive specialization that large-scale industry made possible. The strong increase of the industrial working class and, in general, of the urban population employed in industry and services, which took place in the industrial countries in the last century, could not have taken place if they had not been able to count on the means of subsistence of agricultural origin provided to a considerable extent by the Latin American countries. This was what made it possible to deepen the division of labor and to specialize the industrial countries as world producers of manufactures.

But the role played by Latin America in the development of capitalism was not reduced to this: to its capacity to create a world food supply, which appears as a necessary condition for its insertion in the international capitalist economy, soon was added that of contributing to the formation of a market for industrial raw materials whose importance grows as a function of industrial development itself.10 The growth of the working class in the core countries, and the even more notable rise in its productivity, resulting from the advent of big industry, led to the mass of raw materials poured into the production process to increase in greater proportion.11 This function, which would later reach its fullness, is also the one that would prove to be the most enduring for Latin America, maintaining all its importance even after the international division of labor has reached a new stage.

What is important to consider here is that Latin America’s functions in the world capitalist economy transcend the mere response to the physical requirements induced by accumulation on the industrial countries. Beyond facilitating their quantitative growth, Latin America’s participation in the world market will contribute towards shifting the axis of accumulation in the industrial economy from the production of absolute surplus-value to that of relative surplus-value, that is to say, that accumulation will come to depend more on the increase in the productive capacity of labor than simply on the exploitation of the worker. However, the development of Latin American production, which allows the region to contribute to this qualitative change in the central countries, will be fundamentally based on the greater exploitation of the worker. It is this contradictory character of Latin American dependence which determines the relations of production in the capitalist system as a whole, that should retain our attention.

2) The secret of unequal exchange

The insertion of Latin America into the capitalist economy responds to the demands posed on the industrial countries by the transition to the production of relative surplus-value. This is understood as a form of exploitation of wage labor which, fundamentally based on the transformation of the technical conditions of production, results from the real devaluation of the labor force. Without going too deeply into the question, it is useful to make a few clarifications that relate to our theme.

Essentially, it is a question of dispelling the confusion that is often established between the concept of relative surplus value and that of productivity. Indeed, although it constitutes the condition par excellence of relative surplus-value, a greater productive capacity of labor does not in itself ensure an increase in relative surplus-value. By increasing productivity, the worker only creates more products in the same time, but not more value; it is precisely this fact which leads the individual capitalist to seek an increase in productivity, since it allows him to lower the individual value of his commodity, in relation to the value attributed to it by the general conditions of production, thus obtaining a surplus-value superior to that of his competitors – that is, an extraordinary surplus-value.

Now, this extraordinary surplus-value alters the general distribution of surplus-value among the various capitalists, by being translated into extraordinary profit, but it does not modify the degree of exploitation of labor in the economy or in the branch under consideration, that is to say, it does not affect the share of surplus-value. If the technical procedure which permitted the increase in productivity is generalized to the other enterprises, and therefore the rate of productivity is standardized, this does not entail either an increase in the share of surplus value: the mass of products will only have increased, without varying their value, or what is the same, the social value of the unit of product would be reduced in terms proportional to the increase in the productivity of labor. The consequence would be, then, not the increase of surplus-value, but rather its decrease.

This is because what determines the share of surplus-value is not the productivity of labor per se, but the degree of exploitation of labor, that is, the ratio between surplus labor time (in which the worker produces surplus value) and necessary labor time (in which the worker reproduces the value of his labor-power, that is, the equivalent of his wage).12 Only the alteration of that ratio, in a sense favorable to the capitalist, that is, by increasing surplus labor over necessary labor, can modify the share of surplus-value. For this, the reduction of the social value of commodities must affect goods necessary for the reproduction of labor power, i.e., wage-goods. Relative surplus-value is thus indissolubly linked to the devaluation of wage-goods, for which the productivity of labor generally, but not necessarily, contributes.13

This digression was indispensable if we are to understand why the insertion of Latin America into the world market contributed to the development of the specifically capitalist mode of production which is based on relative surplus-value. We have already mentioned that one of the functions assigned to Latin America within the framework of the international division of labor was to supply the industrial countries with the foodstuffs required by the growth of the working class in particular, and of the urban population in general, that was taking place there. The world food supply, which Latin America helped to create, and which reached its peak in the second half of the 19th century, would be a decisive element for the industrial countries to entrust their subsistence needs to foreign trade.14 The effect of this supply (amplified by the depression of the prices of primary products on the world market, a subject to which we shall return later) will be to reduce the real value of labor power in the industrial countries, thus allowing the increase in productivity to be translated there into higher and higher shares of surplus-value. In other words, through its incorporation into the world wage-goods market, Latin America plays a significant role in the increase of relative surplus value in the industrial countries.

Before examining the other side of the coin, i.e., the internal conditions of production that will allow Latin America to fulfill this function, it should be pointed out that it is not only at the level of its own economy that Latin American dependence reveals itself to be contradictory: Latin America’s participation in the progress of the capitalist mode of production in the industrial countries will, in turn, be contradictory. This is because, as we pointed out earlier, the increase in the productive capacity of labor entails a more than proportional consumption of raw materials. To the extent that this greater productivity is effectively accompanied by greater relative surplus-value, this means that the value of variable capital falls in relation to that of constant capital (which includes raw materials), that is, that the value-composition of capital rises. Now, what the capitalist appropriates is not directly the surplus-value produced, but that part of it which corresponds to him in the form of profit. Since the share of profit cannot be fixed only in relation to the variable capital, but over the total of the capital advanced in the process of production, that is to say, wages, installations, machinery, raw materials, etc., the result of the increase of surplus-value tends to be – provided it implies, even in relative terms, a simultaneous elevation of the value of the constant capital employed to produce it – a lowering of the share of profit.

This contradiction, crucial for capitalist accumulation, is counteracted by various procedures, which, from the strictly productive point of view, are oriented either in the direction of further increasing surplus-value, in order to compensate for the decline in the rate of profit, or in that of inducing a parallel decline in the value of constant capital, with the purpose of preventing the decline from taking place. In the second class of procedures, of interest here is that which refers to the world supply of industrial raw materials, which appears as the counterpart -from the point of view of the composition-value of capital- of the world supply of foodstuffs. As with the latter, it is through the increase of a mass of ever cheaper products on the international market that Latin America not only feeds the quantitative expansion of capitalist production in the industrial countries, but also contributes to overcoming the stumbling blocks that the contradictory character of the accumulation of capital creates for that expansion.15

There is, however, another aspect of the problem that must be considered. This is the well-known fact that the increase in the world supply of food and raw materials has been accompanied by a decline in the prices of these products relative to the price of manufactures.16 Since the price of industrial products remains relatively stable, and in any case declines slowly, the deterioration in the terms of trade is in fact reflecting the depreciation of primary goods. Clearly, such depreciation cannot correspond to the real depreciation of these goods due to an increase in productivity in the non-industrial countries, since it is precisely there that productivity rises more slowly. The reasons for this phenomenon should therefore be explored, as well as the reasons why it did not result in a disincentive for Latin America’s incorporation into the international economy.

The first step in answering this question consists in rejecting the simplistic explanation that only wants to see the result of the law of supply and demand. While it is clear that competition plays a decisive role in price setting, it does not explain why, on the supply side, there is an accelerated expansion regardless of the deterioration of the terms of trade. Nor would it be possible to interpret the phenomenon if we were to limit ourselves to the empirical observation that the laws of trade have been distorted at the international level thanks to diplomatic and military pressure on the part of the industrial nations. Although this reasoning is based on real facts, it inverts the order of the factors and does not see that the use of extra-economic resources derives precisely from the fact that there is behind it an economic base that makes it possible. Both types of explanation contribute, therefore, to hide the nature of the phenomena studied and lead to illusions about what international capitalist exploitation really is.

It is not because the non-industrial nations were abused that they have become economically weak, it is because they were weak that they were abused. Nor is it because they produced more than they should that their commercial position deteriorated, but it was commercial deterioration that forced them to produce on a larger scale. To refuse to see things in this way is to mix up the international capitalist economy, it is to make believe that this economy could be different from what it really is. Ultimately, this leads to claiming equitable trade relations between nations, when what is at issue is the suppression of international economic relations based on exchange value.

Indeed, as the world market attains more developed forms, the use of political and military violence to exploit weak nations becomes superfluous, and international exploitation can progressively rest on the reproduction of economic relations that perpetuate and amplify the backwardness and weakness of those nations. The same phenomenon is observed here as within the industrial economies: the use of force to subject the working masses to the rule of capital diminishes as economic mechanisms come into play that consecrates this subordination.17 The expansion of the world market is the basis on which the international division of labor between industrial and non-industrial nations operates, but the counterpart of this division is the expansion of the world market. The development of mercantile relations lays the foundations for a better application of the law of value to take place, but simultaneously creates all the conditions for the various mechanisms by which capital tries to circumvent it.

Theoretically, the exchange of commodities expresses the exchange of equivalents the value of which is determined by the amount of socially necessary labor embodied in the commodities. In practice, different mechanisms are observed which permit the transfer of value bypassing the laws of exchange, and which are expressed in the way market prices and commodity production prices are fixed. A distinction must be made between mechanisms operating within the same sphere of production (whether of manufactured products or raw materials) and those operating within the framework of different interrelated spheres. In the first case, transfers correspond to specific applications of the laws of exchange; in the second, they take on more openly the character of transgression of these laws.

Thus, as a result of greater productivity of labor, a nation can present lower prices of production than its competitors without significantly lowering the market prices which the conditions of production of the latter help to fix. This is expressed for the favored nation as a windfall profit, similar to that which we observed when we examined the way in which individual capitals appropriate the fruits of the productivity of labor. It is natural that the phenomenon occurs above all at the level of competition among industrial nations, and less so among those producing primary goods, since it is among the former that the capitalist laws of exchange are fully exercised; this does not mean that it does not also occur among the latter, especially when capitalist relations of production develop there.

In the second case -transactions between nations that exchange different kinds of goods, such as manufactures and raw materials- the mere fact that some produce goods that the others do not produce, or cannot produce with the same ease, allows the former to evade the law of value, i.e., to sell their products at prices higher than their value, thus configuring an unequal exchange. This implies that the disadvantaged nations must cede part of the value they produce free of charge, and that this cession or transfer is accentuated in favor of the country that sells them goods at a lower production price, by virtue of its greater productivity. In the latter case, the transfer of value is double, although it does not necessarily appear so for the nation transferring value, since its different suppliers can all sell at the same price, without prejudice to the fact that the profits realized are distributed unequally among them and that the greater part of the value transferred is concentrated in the hands of the country with the highest productivity.

In the presence of these mechanisms of transfer of value, based either on productivity or on the monopoly of production, we can identify – always at the level of international market relations – a mechanism of compensation. This is the recourse to the increase in value exchanged, on the part of the disadvantaged nation: without preventing the transfer operated by the mechanisms already described, this makes it possible to neutralize it totally or partially by means of the increase in the value realized. Such a compensation mechanism can be verified both at the level of the exchange of similar products and of products originating in different spheres of production. We are concerned here only with the second case.

What is important to point out is that in order to increase the mass of value produced the capitalist must necessarily make use of a greater exploitation of labor, either by increasing its intensity, or by prolonging the working day, or by combining the two procedures. Strictly speaking, only the first – the increase in the intensity of labor – really counteracts the disadvantages resulting from a lower productivity of labor, since it permits the creation of more value in the same working time. In fact, they all concur in increasing the mass of value realized and, therefore, the amount of money obtained through exchange. This is what explains, at this level of analysis, that the world supply of raw materials and food increases as the margin between their market prices and the real value of production widens.18

What appears clearly then, is that the nations disadvantaged by unequal exchange do not so much seek to correct the imbalance between the prices and the value of their exported goods (which would imply a redoubled effort to increase the productive capacity of labor), but rather to compensate for the loss of income generated by international trade through recourse to greater exploitation of the worker. We thus arrive at a point where it is no longer sufficient to continue to deal simply with the notion of exchange between nations, but we must face the fact that within the framework of this exchange, the appropriation of the value realized masks the appropriation of a surplus-value which is generated by the exploitation of labor within each nation. From this angle, the transfer of value is a transfer of surplus-value, which appears from the point of view of the capitalist operating in the disadvantaged nation as a lowering of the share of surplus value and hence of the share of profit. Thus, the counterpart of the process by which Latin America contributed to increasing the share of surplus-value and the share of profit in the industrial countries implied for it rigorously opposite effects. And what appeared as a mechanism of compensation of the market mechanism at the level of the market, is in fact a mechanism that operates at the level of domestic production. It is to this sphere that we must therefore shift the focus of our analysis.

3) The super-exploitation of labor

We have seen that the problem posed by unequal exchange for Latin America is not precisely that of counteracting the transfer of value it implies, but rather that of compensating for a loss of surplus-value, and that unable to prevent it at the level of market relations the reaction of the dependent economy is to compensate for it at the level of internal production. The increase in the intensity of labor appears, in this perspective, as an increase in surplus value, achieved through greater exploitation of the worker and not through an increase in his productive capacity. The same could be said of the prolongation of the working day, that is, of the increase of absolute surplus value in its classic form; unlike the former, it is a question here of simply increasing surplus labor time, which is that in which the worker continues to produce after having created a value equivalent to that of the means of subsistence for his own consumption. Finally, a third procedure should be pointed out, which consists in reducing the worker’s consumption beyond its normal limit, whereby “[transforming], within certain limits, the labourer’s necessary consumption fund into a fund for the accumulation of capital,”19 thus implying a specific mode of increasing surplus labor time.

Let us specify here that the use of categories referring to the appropriation of surplus labor in the framework of capitalist relations of production does not imply the assumption that the Latin American export economy is already based on capitalist production. We resort to these categories in the spirit of the methodological observations we made at the beginning of this paper, i.e., because they allow us to better characterize the phenomena we intend to study and also because they indicate the direction in which they are tending. On the other hand, it is not strictly speaking necessary for unequal exchange to exist for the above-mentioned mechanisms of surplus value extraction to come into play; the simple fact of linkage to the world market, and the consequent conversion of the production of use-values to that of exchange values that this entails, has the immediate result of unleashing a drive for profit that becomes all the more unbridled the more backward the existing mode of production is. As Marx points out, “[…] as soon as people, whose production still moves within the lower forms of slave-labour, corvée-labour, &c., are drawn into the whirlpool of an international market dominated by the capitalistic mode of production, the sale of their products for export becoming their principal interest, the civilized horrors of over-work are grafted on the barbaric horrors of slavery, serfdom, &c.”20 The effect of unequal exchange is -to the extent that it places obstacles in the way of its full satisfaction- to exacerbate this desire for profit and thus to sharpen the methods of extracting surplus labor.

Now, the three mechanisms identified -the intensification of labor, the prolongation of the working day and the expropriation of part of the labor necessary for the worker to replace his labor power- make up a mode of production based exclusively on the greater exploitation of the worker and not on the development of his productive capacity. This is congruent with the low level of development of the productive forces in the Latin American economy, but also with the types of activities carried out there. Indeed, more than in manufacturing industry, where an increase in labor implies at least a greater expenditure of raw materials, in the extractive industry and in agriculture the effect of increased labor on the elements of constant capital are much less sensitive, being possible by the simple action of man on nature to increase the wealth produced without additional capital.21 It is understood that in these circumstances, productive activity is based above all on the extensive and intensive use of labor power: this makes it possible to lower the value-composition of capital, which, together with the intensification of the degree of exploitation of labor, causes the quotas of surplus-value and profit to rise simultaneously.

It is also important to point out that, in the three mechanisms considered, the essential characteristic is given by the fact that the worker is denied the conditions necessary to replenish the wear and tear of his labor power: in the first two cases, because he is obliged to a higher expenditure of labor power than he should normally provide, thus causing his premature exhaustion, in the last, because he is deprived even of the possibility of consuming what is strictly indispensable to preserve his labor power in a normal state. In capitalist terms, these mechanisms (which, moreover, can occur, and usually do occur, in combination) mean that labor is remunerated below its value,22 and thus correspond to a super-exploitation of labor.

This is what explains why it was precisely in the zones dedicated to export production that the wage-labor regime was first imposed, initiating the process of transformation of the relations of production in Latin America. It is useful to bear in mind that capitalist production presupposes the direct appropriation of the labor force and not only of the products of labor; in this sense, slavery is a mode of labor that is more suited to capital than servitude and it is no accident that the colonial enterprises directly connected with the European capitalist centers -such as the gold and silver mines of Mexico and Peru, or the sugar plantations of Brazil- were based on slave labor.23 But, except in the hypothesis that the supply of labor is totally elastic (which is not the case beginning in the second half of the 19th century with slave labor in Latin America), the slave labor regime constitutes an obstacle to the indiscriminate lowering of the worker’s remuneration. “In the case of the slave the minimum wage appears as a constant magnitude, independent of his own labour. In the case of the free worker, the value of his labour capacity, and the average wage corresponding to it, does not present itself as confined within this predestined limit, independent of his own labour and determined by his purely physical needs. The average for the class is more or less constant here, as is the value of all commodities; but it does not exist in this immediate reality for the individual worker, whose wage may stand either above or below this minimum.”24 In other words, the regime of slave labor, except under exceptional conditions of the labor market, is incompatible with the super-exploitation of labor. The same is not true of wage labor and, to a lesser extent, of servile labor.

Let us insist on this point. The superiority of capitalism over the other forms of mercantile production and its basic difference in relation to them resides in the fact that what it transforms into merchandise is not the worker -that is, the total time of existence of the worker, with all the dead points that this implies from the point of view of production- but rather his labor power, that is, the time of his usable existence for production, leaving to the same worker the care of taking charge of the non-productive time from the capitalist point of view. This is the reason why, when a slave economy is subordinated to the world capitalist market, the intensification of the exploitation of the slave is accentuated, since it is then in the interest of his owner to reduce his dead time for production and to make productive time coincide with the worker’s time of existence.

But, as Marx points out, “he slave-owner buys his labourer as he buys his horse. If he loses his slave, he loses capital that can only be restored by new outlay in the slave-mart.”25 The super-exploitation of the slave, which prolongs his working day beyond the permissible physiological limits and necessarily results in his premature exhaustion, through death or disability, can only occur if it is possible to easily replace the worn-out labor. “The rice-grounds of Georgia, or the swamps of the Mississippi may be fatally injurious to the human constitution; but the waste of human life which the cultivation of these districts necessitates is not so great that it cannot be repaired from the teeming preserves of Virginia and Kentucky. Considerations of economy, moreover, which, under a natural system, afford some security for humane treatment by identifying the master’s interest with the slave’s preservation, when once trading in slaves is practiced, become reasons for racking to the uttermost the toil of the slave; for, when his place can at once be supplied from foreign preserves, the duration of his life becomes a matter of less moment than its productiveness while it lasts.”26 The contrary evidence proves the same thing: in Brazil in the second half of the last century, when the coffee boom was beginning, the fact that the slave trade had been suppressed in 1850 made slave labor so unattractive to landowners in the south that they preferred to turn to the salaried regime through European immigration, in addition to favoring a policy tending to suppress slavery. Let us remember that an important part of the slave population was located in the decadent sugar producing area of the northeast and that the development of agrarian capitalism in the south imposed its liberation in order to constitute a free labor market. The creation of this market with the law abolishing slavery in 1888 which culminated a series of gradual measures in this direction (such as the status of free man granted to the children of slaves, etc.) constitutes a phenomenon as far as we can see of a free labor market. On the one hand, it was defined as an extremely radical measure that liquidated the foundations of imperial society (the monarchy survived the law of 1888 by little more than a year) and went so far as to deny any compensation to former slave owners. On the other hand, it sought to compensate for the impact of its effect through measures aimed at tying the worker to the land (the inclusion of an article in the civil code that tied the debts contracted to the person; the “barracão” system, a true monopoly of trade in consumer goods exercised by the large landowner within the estate, etc.) and the granting of generous credits to the affected landowners.

The mixed system of serfdom and wage labor established in Brazil, with the development of the export economy for the world market, is one of the ways in which Latin America arrived at capitalism. Let us observe that the form adopted by the relations of production, in this case, does not differ much from the labor regime established, for example, in the Chilean saltpetre mines, whose “token system” is equivalent to the “barracão“. In other situations, which occur above all in the process of subordination of the interior to the export zones, the relations of exploitation can present themselves more clearly as servile relations, without this obstructing that through the extortion of the surplus product from the worker by the action of commercial or usurious capital, the worker is involved in a direct exploitation by capital which even tends to assume a character of super-exploitation.27 However, servitude presents for the capitalist the disadvantage that it does not allow him to directly direct production, besides always raising the possibility, even if only theoretical, of the immediate producer emancipating himself from the dependence in which he is placed by the capitalist.

It is not, however, our purpose here to study the particular economic forms that existed in Latin America before it effectively entered the capitalist stage of production, nor the ways in which the transition took place. What we intend is only to set the pattern in which this study is to be carried out, a pattern that corresponds to the real movement of the formation of dependent capitalism: from circulation to production, from the link to the world market to the impact that this has on the internal organization of labor, and then to rethink the problem of circulation. For it is proper to capital to create its own mode of circulation, and/or on this depends the expanded reproduction on a world scale of the capitalist mode of production:

[…] since capital alone possesses the conditions of the production of capital, hence satisfies and strives to realize [them], [it is] a general tendency of capital at all points which are presuppositions of circulation, which form its productive centres, to assimilate these points into itself, i.e. to transform them into capitalizing production or production of capital.28

Once converted into a capital-producing center, Latin America will thus have to create its own mode of circulation which cannot be the same as that which was engendered by industrial capitalism and which gave rise to dependency. In order to constitute a complex whole, it is necessary to resort to simple elements that can be combined, but which are not the same. Therefore, understanding the specificity of the cycle of capital in the Latin American dependent economy means illuminating the very foundation of its dependence in relation to the world capitalist economy.

4) The capital cycle in the dependent economy

By developing its mercantile economy in the function of the world market, Latin America is led to reproduce within itself the relations of production that were at the origin of the formation of that market and which determined its character and expansion.29 But this process was marked by a profound contradiction: called upon to contribute to the accumulation of capital based on the productive capacity of labor in the central countries, Latin America had to do so through an accumulation based on the super-exploitation of the worker. In this contradiction lies the essence of Latin American dependence.

The real basis on which it develops are the ties that bind the Latin American economy to the world capitalist economy. Born to meet the demands of capitalist circulation, whose axis of articulation is constituted by the industrial countries, and thus centered on the world market, Latin American production does not depend for its realization on the internal capacity for consumption. Thus, from the point of view of a dependent country, the separation of the two fundamental moments of the cycle of capital – production and circulation of merchandise – takes place, the effect of which is to make appear in a specific way in the Latin American economy the contradiction inherent to capitalist production in general, that is to say, that which opposes capital to the worker as seller and buyer of merchandise.30 The contradiction between capital and the worker as a seller and buyer of merchandise is the same as the contradiction inherent to capitalist production in general, that is to say, that which opposes capital to the worker as seller and buyer of merchandise.

This is a key point for understanding the character of the Latin American economy. Initially, it must be considered that in industrial countries whose capital accumulation is based on the productivity of labor, this opposition generated by the dual character of the worker -producer and consumer- although effective, is to some extent counteracted by the form assumed by the cycle of capital. Thus, although capital privileges the productive consumption of the worker (that is, the consumption of the means of production involved in the labor process), and is inclined to disregard his individual consumption (which the worker uses to replenish his labor-power) which appears to him as unproductive consumption,31 this occurs exclusively at the moment of production. When the phase of realization opens, this apparent contradiction between the individual consumption of the workers and the reproduction of capital disappears, once this consumption (added to that of the capitalists and of the unproductive layers in general) restores to capital the form that is necessary for it to begin a new cycle, i.e. the money form. The individual consumption of the workers thus represents a decisive element in the creation of demand for the commodities produced, being one of the conditions for the flow of production to be adequately resolved in the flow of circulation.32 Through the mediation established by the struggle between workers and bosses over the fixing of the level of wages, the two types of consumption of the worker thus tend to complement each other, in the course of the cycle of capital, overcoming the initial situation of opposition in which they found themselves. This is, moreover, one of the reasons why the dynamics of the system tends to be channeled through relative surplus-value, which implies in the last analysis, the cheapening of the commodities that enter into the composition of the worker’s individual consumption.

In the Latin American export economy, things are different. Since circulation is separated from production and takes place basically in the sphere of the external market, the individual consumption of the worker does not interfere in the realization of the product, although it does determine the share of surplus-value. Consequently, the natural tendency of the system will be to exploit to the maximum the labor force of the worker, without worrying about creating the conditions for him to replace it, as long as he can be replaced by incorporating new arms to the productive process. The dramatic thing for the working population of Latin America is that this assumption was amply fulfilled: the existence of reserves of indigenous labor (as in Mexico) or the migratory flows derived from the displacement of European labor caused by technological progress (as in South America) allowed for a constant increase in the mass of workers until the beginning of this century. The result has been to give free rein to the compression of the individual consumption of the worker and, therefore, to the super-exploitation of labor.

The export economy is, then, something more than the product of an international economy founded on productive specialization: it is a social formation based on the capitalist mode of production, which accentuates to the limit the contradictions inherent to it. In doing so, it configures in a specific way the relations of exploitation on which it is based, and creates a cycle of capital that tends to reproduce on an enlarged scale the dependence in which it finds itself vis-à-vis the international economy.

Thus, the sacrifice of workers’ individual consumption for the sake of exporting to the world market depresses the levels of domestic demand and makes the world market the only outlet for production. At the same time, the resulting increase in profits puts the capitalist in a position to develop consumption expectations without a counterpart in domestic production (oriented towards the world market), expectations that have to be satisfied through imports. The separation between individual consumption based on wages and individual consumption generated by unaccumulated surplus-value thus gives rise to a stratification of the internal market, which is also a differentiation of spheres of circulation: while the “low” sphere, in which workers participate -which the system strives to restrict- is based on internal production, the “high” sphere of circulation, proper to non-workers -which is what the system tends to widen- is linked to external production, through the import trade.

The harmony established, at the level of the world market, between the export of raw materials and foodstuffs by Latin America and the import of European manufactured consumer goods conceals the dilaceration of the Latin American economy expressed by the division of total individual consumption into two opposing spheres. When the world capitalist system reaches a certain stage of development and Latin America enters the stage of industrialization it will have to do so on the basis of the foundations created by the export economy. The profound contradiction that will have characterized the capital cycle of that economy and its effects on the exploitation of labor will have a decisive influence on the course that the Latin American industrial economy will take explaining many of the problems and tendencies that are present in it today.

5) The industrialization process

It is not appropriate here to analyze the industrialization process in Latin America or much less to take sides in the current controversy on the role played by import substitution in this process.33 For the purposes we have proposed, it is sufficient to note that however significant industrial development may have been within the export economy (and, consequently, in the extension of the domestic market), in countries such as Argentina, Mexico, Brazil and others, it never managed to form a true industrial economy which by defining the character and direction of capital accumulation would bring about a qualitative change in the economic development of these countries. On the contrary, industry continued to be an activity subordinated to the production and export of primary goods, which constituted the vital center of the accumulation process.34 It was only when the crisis of the international capitalist economy, corresponding to the period between the First and Second World Wars, hindered accumulation based on production for the external market that the axis of accumulation shifted towards industry, giving rise to the modern industrial economy that prevailed in the region.

From the point of view that interests us, this means that the upper sphere of circulation, which was articulated with the external supply of manufactured consumer goods, shifts its center of gravity towards domestic production, its parabola coinciding roughly with the one described by the lower sphere proper to the working masses. It would seem that the eccentric movement of the export economy was beginning to be corrected, and that dependent capitalism was moving in the direction of a configuration similar to that of the classic industrial countries. It was on this basis that in the 1950s the various so-called developmentalist currents flourished, which assumed that the economic and social problems afflicting the Latin American social formation were due to an insufficiency of its capitalist development, and that the acceleration of this development would be enough to make them disappear.

In fact, the apparent similarities of the dependent industrial economy with the classical industrial economy concealed profound differences, which capitalist development would accentuate rather than attenuate. The inward reorientation of demand generated by unaccumulated surplus-value already implied a specific mechanism of internal market creation radically different from that operating in the classical economy and which would have serious repercussions on the form that the dependent industrial economy would assume.

In the classical capitalist economy, the formation of the internal market represents the counterpart of the accumulation of capital: by separating the producer from the means of production capital not only creates the wage earner, that is, the worker who has only his labor power at his disposal, but also creates the consumer. In effect, the means of subsistence of the worker, previously produced directly by him, are incorporated into capital, as a material element of variable capital, and are only returned to the worker once he purchases their value in the form of wages.35 There is, then, a close correspondence between the rhythm of accumulation and that of the expansion of the market. The possibility for the industrial capitalist to obtain abroad, at a low price, the food necessary for the worker, leads to a narrowing of the nexus between accumulation and the market, once the part of the worker’s individual consumption dedicated to the absorption of manufactured products increases. That is why industrial production in this type of economy, is basically centered on goods of popular consumption and seeks to make them cheaper, since they directly affect the value of labor power and therefore -insofar as the conditions in which the struggle between workers and bosses takes place tends to bring wages closer to that value- the share of surplus-value. We have already seen that this is the fundamental reason why the classical capitalist economy must be oriented towards increasing the productivity of labor.

The development of accumulation based on the productivity of labor results in the increase of surplus-value, and, consequently, of the demand created by the part of it that does not accumulate. In other words, the individual consumption of the non-producing classes grows, thus widening the sphere of circulation that corresponds to them. This drives not only the growth of the production of manufactured consumer goods in general, but also that of the production of sumptuary articles.36 Circulation thus tends to split into two spheres, similar to what we see in the Latin American export economy, but with a substantial difference: the expansion of the upper sphere is a consequence of the transformation of the conditions of production, and becomes possible to the extent that, as the productivity of labor increases, the part of total individual consumption which corresponds to the worker decreases in real terms. The existing link between the two spheres of consumption is loosened, but not broken.

Another factor helps to prevent the rupture from taking place: it is the way in which the world market is expanding. The additional demand for sumptuary products created by the foreign market is necessarily limited, first because, when trade is between nations producing such goods, the advance of one nation implies the retreat of another, which gives rise on the part of the latter to defense mechanisms; and then because, in the case of exchange with dependent countries, this demand is restricted to the upper classes, and is thus constrained by the strong concentration of income implied by the super-exploitation of labor. In order for the production of luxury goods to expand, these goods must change their character, that is, become products of popular consumption within the industrial economy itself. The circumstances that made it possible to raise real wages there, beginning in the second half of the last century, to which the devaluation of foodstuffs and the possibility of redistributing internally part of the surplus subtracted from the dependent nations are not unrelated, help, insofar as they expand the individual consumption of workers, to counteract the disruptive tendencies that act at the level of circulation. Latin American industrialization37 is based on different foundations. The permanent compression exerted by the export economy on individual worker consumption only allowed the creation of a weak industry, which only expanded when external factors (such as trade crises, temporarily, and the limitation of trade balance surpluses, for the reasons already mentioned) partially closed the access of the upper sphere of consumption to import trade.38 It is the greater incidence of these factors, as we have seen, which accelerates industrial growth, from a certain moment on, and provokes the qualitative change of dependent capitalism. Therefore, Latin American industrialization does not create, as in the classical economies, its own demand, but is born to meet a pre-existing demand, and will be structured according to the market requirements coming from the advanced countries.

At the beginning of industrialization, the participation of workers in the creation of demand did not play a significant role in Latin America. Operating within the framework of a previously given market structure, whose price level acted in the sense of preventing access to popular consumption, industry had no reason to aspire to a different situation. The demand capacity was, at that time, greater than the supply, so that the capitalist did not face the problem of creating a market for his goods, but rather the reverse situation. On the other hand, even when supply comes to equilibrium with demand -which will occur later- this will not immediately present the capitalist with the problem of expanding the market, leading him first to play on the margin between the market price and the price of production, that is, on the increase of the mass of profit as a function of the unit price of the product. For this, the industrial capitalist will force, on the one hand, the rise in prices, taking advantage of the monopolistic situation created de facto by the crisis of world trade and reinforced by customs barriers. On the other hand, and given that the low technological level means that the price of production is determined fundamentally by wages, the industrial capitalist will take advantage of the surplus labor created by the exporting economy itself and aggravated by the crisis it is experiencing (a crisis which forces the exporting sector to free up labor), to put downward pressure on wages. This will allow it to absorb large masses of labor, which, accentuated by the intensification of work and the lengthening of the working day, will accelerate the concentration of capital in the industrial sector.

Starting then from the mode of circulation which characterized the export economy, the dependent industrial economy reproduces, in a specific form, the accumulation of capital based on the super-exploitation of the worker. Consequently, it also reproduces the mode of circulation that corresponds to this type of accumulation, albeit in a modified form: it is no longer the dissociation between the production and circulation of commodities in function of the world market that operates, but the separation between the upper and lower spheres of circulation within the economy itself. A separation which, not being counteracted by the factors at work in the classical capitalist economy, acquires a much more radical character.

Dedicated to the production of goods that do not enter, or enter very scarcely, into the composition of popular consumption, Latin American industrial production is independent of the wage conditions proper to the workers; this in two senses. In the first place because, not being an essential element of the individual consumption of the worker, the value of manufactures does not determine the value of labor power; it will not be, then, the devaluation of manufactures that will influence the share of surplus-value. This dispenses the industrialist from worrying about increasing the productivity of labor in order, by lowering the value of the unit of product, to depreciate the labor force, and leads him, inversely, to seek to increase surplus value through greater exploitation -intensive and extensive- of the worker, as well as the lowering of wages beyond their normal limit. In the second place, because the inverse relation which is derived therefrom for the evolution of the supply of commodities and the purchasing power of the workers, that is to say, the fact that the former grows at the cost of the reduction of the latter, does not create problems for the capitalist in the sphere of circulation, once, as we noted, manufactures are not essential elements in the individual consumption of the worker’s individual consumption.

We said earlier that at a certain point in the process, which varies from country to country,39 the industrial supply coincides roughly with the existing demand, constituted by the upper sphere of circulation. The need then arises to generalize the consumption of manufactured goods, which corresponds to the moment when, in the classical economy, sumptuary goods had to be converted into goods for popular consumption. This gives rise to two types of adaptations in the dependent industrial economy: the expansion of consumption by the middle strata, which is generated from unaccumulated surplus value, and the effort to increase the productivity of labor, a sine qua non condition for lowering the price of merchandise.

The second movement would normally tend to bring about a qualitative change in the basis of capital accumulation, allowing the individual consumption of the worker to modify its composition and include manufactured goods. If it acted alone, it would lead to the displacement of the axis of accumulation, from the exploitation of the worker to the increase in the productive capacity of labor. However, it is partially neutralized by the expansion of consumption of the middle sectors: this presupposes, in effect, the increase in the income received by these sectors, income which, as we know, derives from surplus value and, consequently, from the compression of the wage level of the workers. The transition from one mode of accumulation to another is therefore difficult and takes place extremely slowly, but it is enough to trigger a mechanism that will eventually act in the sense of hindering the transition, diverting the search for solutions to the problems of realization faced by the industrial economy into a new channel.

This mechanism is the recourse to foreign technology, aimed at raising the productive capacity of labor.

6) The new spiral ring

It is a well-known fact that, as Latin American industrialization progresses, the composition of its imports is altered, through the reduction of consumer goods and their replacement by raw materials, semi-finished products and machinery for industry. However, the permanent crisis in the external sector of the countries of the region would not have allowed the growing needs in material elements of constant capital to be satisfied exclusively through commercial exchange. This is why the importation of foreign capital, in the form of financing and direct investments in industry, became so important.

The facilities that Latin America finds abroad to resort to the importation of capital are not accidental. They are due to the new configuration assumed by the international capitalist economy in the post-war period. By 1950, it had overcome the crisis that had affected it since the 1910s and was already reorganized under the aegis of the United States. The progress achieved by the concentration of capital on a world scale placed an abundance of resources in the hands of the large imperialist corporations, which needed to seek application abroad. The significant feature of the period is that this flow of capital to the periphery is preferentially oriented towards the industrial sector.

This is due to the fact that, during the period of disorganization of the world economy, peripheral industrial bases were developed, which offered -thanks to the super-exploitation of labor- attractive possibilities of profit. But this was not the only fact, and perhaps not the most decisive. In the course of the same period, there had been a great development of the capital goods sector in the central economies. This led, on the one hand, to the fact that the equipment produced there, always more sophisticated, had to be applied in the secondary sector of the peripheral countries; the central economies were then interested in promoting the industrialization process in these countries, with the aim of creating markets for their heavy industry. On the other hand, to the extent that the pace of technical progress in the central countries reduced the replacement period of fixed capital by almost half,40 these countries were faced with the need to export to the periphery equipment and machinery that were already obsolete before they had been fully depreciated.

Latin American industrialization thus corresponds to a new international division of labor, in the framework of which the lower stages of industrial production are transferred to the dependent countries (note that the iron and steel industry, which was a distinctive sign of the classical industrial economy, has been generalized to the point that countries like Brazil already export steel), reserving for the imperialist centers the more advanced stages (such as the production of computers and the heavy electronics industry in general, the exploitation of new sources of energy, such as nuclear energy, etc.) and the monopoly of the corresponding technology. Going even further, it is possible to distinguish in the international economy steps in which not only the new industrial countries, but also the older ones, are repositioned. Thus, in the production of steel and motor vehicles, Western Europe and Japan compete advantageously with the United States itself, but have not yet succeeded in doing so in the machine-tool industry, especially the automated ones.41 What we have here is a new hierarchization of the world capitalist economy, the basis of which is the redefinition of the international division of labor that has taken place over the last fifty years.

In any case, the moment when the dependent industrial economies look abroad for the technological instruments that will enable them to accelerate their growth by increasing labor productivity is also the moment when important flows of capital originate from the central countries that provide them with the required technology flow to them. We will not examine here the effects of the different forms of technological absorption, ranging from donations to direct investment of foreign capital, since, from the point of view guiding our analysis, this is of little importance. We will deal only with the nature of this technology and its impact on market expansion.

Technological progress is characterized by the saving of labor power which, either in terms of time or in terms of effort, the worker must devote to the production of a certain mass of goods. It is natural, then, that, globally, its result is the reduction of productive labor time in relation to the total time available for production, which, in capitalist society, is manifested through the decrease of the working population in parallel with the growth of the population engaged in non-productive activities, to which services correspond, as well as of the parasitic strata, which are exempted from any participation in the social production of goods and services. This is the specific form that technological development assumes in a society based on the exploitation of labor, but not the general form of technological development. It is for this reason that the recommendations made to dependent countries, in which there is a great availability of labor, to adopt technologies that incorporate more labor force, in order to defend employment levels, represent a double deception: they lead to advocate the option for less technological development and confuse the specifically capitalist social effects of technology with the technology itself.

These recommendations, moreover, ignore the concrete conditions under which technical progress is introduced in dependent countries. This introduction depends, as we have pointed out, less on their preferences than on the objective dynamics of capital accumulation on a world scale. It was this that pushed the international division of labor to assume a configuration, in the framework of which new channels have been opened to the diffusion of technical progress and this has been given a more accelerated pace. The effects derived therefrom for the situation of workers in the dependent countries could not differ in essence from those inherent to a capitalist society: reduction of the productive population and growth of the non-productive social strata. But these effects would have to be modified by the conditions of production proper to dependent capitalism.

Thus, by influencing a productive structure based on the greater exploitation of the workers, technical progress made it possible for the capitalist to intensify the rate of labor of the worker, raise his productivity and simultaneously, sustain the tendency to remunerate him at a lower rate than his real value. A decisive factor in this was the linking of the new techniques of production to industrial branches oriented towards types of consumption which, if they tend to become popular consumption in the advanced countries, cannot do so under any circumstances in dependent societies. The gulf existing there between the standard of living of the workers and that of the sectors that feed the upper sphere of circulation makes it inevitable that products such as automobiles, household appliances, etc., are necessarily destined for the latter. To this extent, and since they do not represent goods which intervene in the consumption of the workers, the increase in productivity induced by technology in these branches of production has not been able to be translated into greater profits through the increase in the share of surplus-value, but only through the increase in the mass of realized value. The spread of technical progress in the dependent economy will thus go hand in hand with greater exploitation of the worker, precisely because accumulation continues to depend fundamentally more on the increase of the mass of value – and therefore of surplus value – than on the share of surplus-value.

However, since technological development was highly concentrated in the branches producing luxury goods, it would end up posing serious problems of realization. The recourse used to solve them has been to involve the State (through the expansion of the bureaucratic apparatus, subsidies to producers and the financing of luxury consumption), as well as inflation, in order to transfer purchasing power from the lower to the upper sphere of circulation; this implied lowering real wages even further, in order to have sufficient surplus to carry out the transfer of income. But, to the extent that the consumption capacity of the workers is thus compressed, any possibility of stimulating technological investment in the sector of production destined to serve popular consumption is closed off. It is therefore not surprising that, while the luxury goods industries are growing at high rates, the industries oriented towards mass consumption (the so-called “traditional industries”) are tending to stagnate and even regress.

Insofar as it occurred with difficulty and at an extremely slow pace, the tendency towards rapprochement between the two spheres of circulation, which had been observed from a certain point onwards, could not continue to develop. On the contrary, what is imposed is once again the repulsion between the two spheres, once the compression of the standard of living of the working masses becomes the necessary condition of the expansion of the demand created by the strata living on surplus-value. Production based on the super-exploitation of labor thus engendered again the mode of circulation that corresponds to it, at the same time divorcing the productive apparatus from the consumption needs of the masses. The stratification of this apparatus into what has come to be called “dynamic industries” (branches producing sumptuary goods and capital goods destined principally for these) and “traditional industries” is reflecting the adaptation of the structure of production to the structure of circulation proper to dependent capitalism.

But the reapproximation of the dependent industrial model to that of the export economy does not stop there. The absorption of technical progress in conditions of super-exploitation of labor brings with it the inevitable restriction of the internal market, which is opposed to the need to realize ever-increasing masses of value (since accumulation depends more on the mass than on the quota of surplus value). This contradiction could not be resolved by extending the upper sphere of consumption within the economy, beyond the limits set by super-exploitation itself. In other words, not being able to extend to the workers the creation of demand for sumptuary goods, and orienting itself instead towards wage compression, which excludes them de facto from this type of consumption, the dependent industrial economy not only had to rely on an immense reserve army, but was obliged to restrict to the capitalists and upper middle strata the realization of luxury goods. This will raise, from a certain moment (which is clearly defined in the mid-1960s), the need to expand outwards, that is to say, to unfold again -although now from the industrial base- the capital cycle, to partially focus the circulation on the world market. The export of manufactured goods, both essential goods and luxury products, then becomes the lifeline of an economy unable to overcome the disruptive factors that afflict it. From regional and subregional economic integration projects to the design of aggressive international competition policies, Latin America is witnessing the resurrection of the old export economy model.

In recent years, the accentuated expression of these tendencies in Brazil has led us to speak of sub-imperialism.42 We do not intend to return to the subject here, since the characterization of sub-imperialism goes beyond simple economics, and cannot be carried out without recourse to sociology and politics. We will limit ourselves to indicating that, in its broadest dimension, sub-imperialism is not a specifically Brazilian phenomenon, nor does it correspond to an anomaly in the evolution of dependent capitalism. It is true that it is the conditions proper to the Brazilian economy, which have allowed it to carry its industrialization to a great extent and even to create a heavy industry, as well as the conditions characterizing its political society, whose contradictions have given rise to a militaristic State of Prussian type, which have given rise to sub-imperialism in Brazil, but it is no less true that this is only a particular form assumed by the industrial economy which develops within the framework of dependent capitalism. In Argentina or El Salvador, in Mexico, Chile, Peru, the dialectic of dependent capitalist development is not essentially different from the one we are trying to analyze here, in its most general features.

To use this line of analysis to study the concrete social formations of Latin America, to orient this study in the sense of defining the determinations that are at the base of the class struggle that unfolds there and thus open up clearer perspectives for the social forces bent on destroying this monstrous formation that is dependent capitalism: this is the theoretical challenge that is posed today to Latin American Marxists. The answer we give will undoubtedly influence in a not inconsiderable way the final outcome of the political processes we are living.

Postscript

Initially, my intention was to write a preface to the preceding essay. But it is difficult to present a work that is in itself a presentation. And Dialectics of Dependency is intended to be nothing more than this: an introduction to the research theme that has been occupying me and the general lines that guide me in this work. Its publication obeys the purpose of advancing some of the conclusions I have reached, which may perhaps contribute to the efforts of others who are dedicated to the study of the laws of development of dependent capitalism, as well as the desire to give myself the opportunity to take a global look at the terrain I am trying to unravel. I will therefore take advantage of this post-scriptum to clarify a few questions and clear up certain misunderstandings that the text has given rise to. Indeed, despite the care taken to qualify the most categorical statements, the limited scope of the text has led to the trends analyzed being painted in broad strokes, which has sometimes given them a very marked profile. On the other hand, the very level of abstraction of the essay was not conducive to the examination of particular situations, which would allow a certain degree of relativization to be introduced into the study. Without pretending to justify myself with this, the aforementioned drawbacks are the same to which Marx alludes, when he warns:

… in theory it is assumed that the laws of capitalist production operate in their pure form. In reality there exists only approximation; but, this approximation is the greater, the more developed the capitalist mode of production and the less it is adulterated and amalgamated with survivals of former economic conditions.43

Now, a first point to note is precisely that the tendencies pointed out in my essay have a different impact on the different Latin American countries according to the specificity of their social formation. It is likely that, due to my shortcoming, the reader will not notice one of the assumptions that inform my analysis: that the export economy constitutes the transition stage to an authentic national capitalist economy, which only takes shape when the industrial economy emerges there44, and that the survival of the old modes of production that governed the colonial economy still determine to a considerable degree the way in which the laws of development of dependent capitalism are manifested in these countries. The importance of the slave regime of production in determining the current economy of some Latin American countries such as Brazil is a fact that cannot be ignored.

A second problem refers to the method used in the essay, which is made explicit in the indication of the need to start from circulation to production, in order to then undertake the study of the circulation that this engenders. This method, which has raised some objections, corresponds rigorously to the path followed by Marx. Suffice it to recall how in Capital, the first sections of Book I are devoted to problems proper to the sphere of circulation and only from the third section onwards does the study of production begin. Likewise, once the examination of general questions has been completed, the particular questions of the capitalist mode of production are analyzed in the same way in the following two books. Beyond the simple formal ordering of the exposition, this has to do with the essence of the dialectical method itself, which makes the theoretical examination of a problem coincide with its historical development. It is thus how this methodological orientation not only corresponds to the general formula of capital, but also accounts for the transformation of simple mercantile production into capitalist mercantile production.

The sequence applies with all the more reason when the object of study is the dependent economy. Let us not insist here on the emphasis that traditional studies on dependency give to the role played in it by the world market or, to use developmentalist language, the external sector. Rather, let us emphasize what constitutes one of the central themes of the essay: at the beginning of its development, the dependent economy is entirely subordinated to the dynamics of accumulation in the industrial countries, to such an extent that it is in function of the downward trend of the rate of profit in these countries, that is, of the way in which capital accumulation is expressed there,45 that such development can be explained. It is only as the dependent economy becomes in fact a true center of capital production, which brings with it its phase of circulation46 – which reaches maturity with the constitution of an industrial sector- that its laws of development, which always represent a particular expression of the general laws governing the system as a whole, are fully manifested in it. From that moment on, the phenomena of circulation that arise in the dependent economy cease to correspond primarily to problems of realization of the industrial nation to which it is subordinated and become more and more problems of realization referring to its own cycle of capital.