Date: July 4, 2019

Author: Paul Cockshott

1 Introduction

Louis Althusser is a controversial figure: murderer, one time communist philosopher, massive guru to generations of cultural studies authors. His key paper on ideology[2] has, according to Google Scholar, been cited over thirteen thousand times1.

He is clearly a very influential philosopher. But here is the paradox. He made his name as a stubbornly orthodox Marxist Leninist within the PCF arguing for orthodox interpretations of Marx and against the humanist and Hegelian interpretations that were briefly fashionable in the post 1956 aftermath of de-Stalinisation. From the late 60s he sided, theoretically, with the Maoists within the international communist movement. For example his Contradiction and Over-determination[1] was an extended essay on Mao’s On Contradiction[7]. With the growth of a Maoist opposition within the PCF and the subsequent influence of former students and colleagues of his in independent Maoist groups his intellectual influence as a bastion of Marxist Leninist philosophy grew.

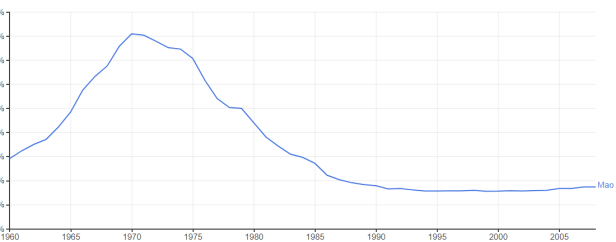

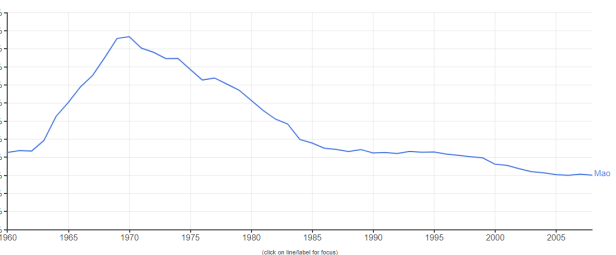

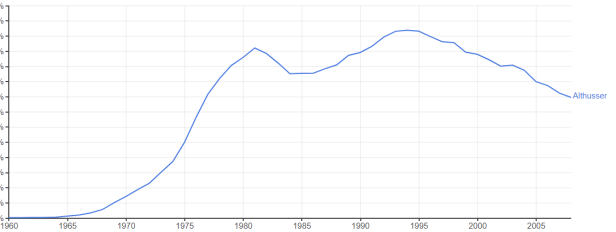

Figure 1: The citation frequency of Mao (top) and Althusser (bottom) in French were closely correlated up to the 1990s. This indicates how during the heyday of French Maoism he was associated with it as an ideological movement. Data from Google Ngram searches.

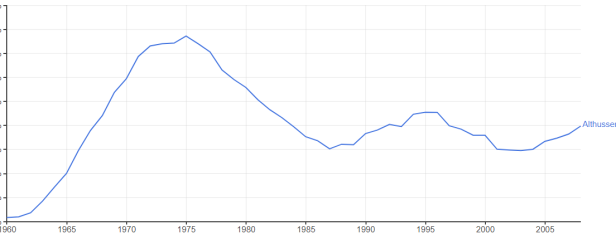

Figure 2: The decline in communist voting strength in France. Source Alankazame and Wikipedia.

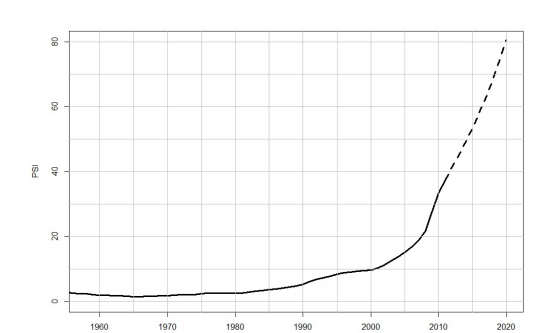

Figure 3: The citation frequency of Mao (top) and Althusser (bottom) in English were correlated only up to 1970. This indicates that in the English speaking world interest in Althusser was quote detached from support for hard-line communism. Contrast this with the French data shown in Figure 1. Data from Google Ngram search .1

In France, he lost intellectual influence with the collapse of the Maoist movement and the decline of the PCF. Figures 1 and 2 show how interest in Althusser paralleled interest in Mao, and, in France at least, declined with the decline in support for communism.

But look at his reception in the English speaking world. Far from interest declining after 1970, when the brief Anglo Saxon interest in Maoism petered out, Althusserianism prospered, not peaking until 1995. Was this a sign of a burgeoning communist politics in Britain and the USA?

Was Marxist Leninist orthodoxy establishing itself in the colleges of these countries?

Clearly not, as anyone familiar with the UK or USA during the 1980s or 1990s will know. This was a period when the labour movement was in retreat, when ideologies of the free market were dominant in politics, including within the official parties of the left. They were the years in which the USSR collapsed, the CPGB dissolved itself, and Fukuyama proclaimed the end of history. For the French, Althusser was the philosopher of the militant labour movement, for the English he was the philosopher of literary theory and discourse analysis, of a Left that was based in the universities. Not only a university left, but one that, by its concerns, was effectively isolating itself from the great political and economic issues of the day. Instead of analyzing British economics, foreign or military policy, it concerned itself with literature, film and gender. Whilst Thatcher proclaimed ’there is no alternative’ to the free market, British Althusserian applied what they called cultural materialism to the works of Shakespeare. Why this concern with classical literature:

Societies need to produce materially to continue – they need food, shelter, warmth; goods to exchange with other societies; a transport and information infrastructure to carry those processes. Also, they have to produce ideologically (Althusser makes this argument at the start of his essay on ideological state apparatuses). They need knowledges to keep material production going – diverse technical skills and wisdoms in agriculture, industry, science, medicine, economics, law, geography, languages, politics, and so on. And they need understandings, intuitive and explicit, of a system of social relationships within which the whole process can take place more or less evenly. Ideology produces, makes plausible, concepts and systems to explain who we are, who the others are, how the world works.

The strength of ideology derives from the way it gets to be common sense; it “goes without saying.”

….

The conditions of plausibility are therefore crucial. They govern our understandings of the world and how to live in it, thereby seeming to define the scope of feasible political change. Most societies retain their current shape, not because dissidents are penalized or incorporated, though they are, but because many people believe that things have to take more or less their present form – that improvement is not feasible, at least through the methods to hand.[9]

This passage, from an article on Othello, captures well the Althusserian justification that a generation of English Marxists used for their retreat from politics to literature. In the argument, I present below we will see that Sinfield’s take on Althusser is not unfair. I will argue that whilst Althusser’s starting point when discussing ideology was politically sound, he ended up with a theory that is a mishmash of genuine insights mixed with a mass of speculative nonsense.

So what is Althusser’s theory?

The components of his argument were:

• The reproduction standpoint,

• The state machine,

• The ideological state machine,

• The constitution of the subject.

He starts out by observing that one of the key advances in Marx’s Capital was the analysis of reproduction in Volume 2. This analyzed how both the material elements of production and the ownership relations are reproduced by the exchange between sectors of the economy. Althusser then observes that any social reproduction has to be both a material reproduction and a reproduction of social relations.

It follows that, in order to exist, every social formation must reproduce the conditions of its production at the same time as it produces, and in order to be able to produce. It must therefore reproduce:

1. The productive forces,

2. The existing relations of production.[2]

Having briefly discussed the reproduction of the productive forces2 he goes on to discuss the problem of the reproduction of labour power.

How is the reproduction of labour power ensured? It is ensured by giving labour power the material means with which to reproduce itself: by wages.

He mentions that the wage must be sufficient not only to reproduce the employees on a daily basis but has to be enough to support a new generation of workers. This, it may be noted is a rather teleological assumption, also made by Marx. There is no guarantee that wages or the combination of wages and working hours, will actually allow the reproduction of the next generation – as experience in Japan in the last decade shows.

He then says that not only must the next generation exist, but it must also be educated and given the necessary know-how to be productive workers. Beyond this the school system must train them in submission or domination:

But besides these techniques and knowledge, and in learning them, children at school also learn the ‘rules’ of good behavior, i.e. the attitude that should be observed by every agent in the division of labour, according to the job he is ‘destined’ for: rules of morality, civic and professional conscience, which actually means rules of respect for the socio-technical division of labour and ultimately the rules of the order established by class domination. They also learn to ‘speak proper French’, to ‘handle’ the workers correctly, i.e. actually (for the future capitalists and their servants) to ‘order them about’ properly, i.e. (ideally) to ‘speak to them’ in the right way, etc.

To put this more scientifically, I shall say that the reproduction of labour power requires not only a reproduction of its skills, but also, at the same time, a reproduction of its submission to the rules of the established order, i.e. a reproduction of submission to the ruling ideology for the workers, and a reproduction of the ability to manipulate the ruling ideology correctly for the agents of exploitation and repression, so that they, too, will provide for the domination of the ruling class ‘in words’.

And slightly later he writes:

The reproduction of labour power thus reveals as its sine qua non not only the reproduction of its ‘skills’ but also the reproduction of its subjection to the ruling ideology or of the ‘practice’ of that ideology, with the proviso that it is not enough to say ‘not only but also,’ for it is clear that it is in the forms and under the forms of ideological subjection that provision is made for the reproduction of the skills of labour power. But this is to recognize the effective presence of a new reality: ideology.

Whilst, at first sight, this seems plausible, is it correct?

Whilst Althusser makes a smooth transition from

1. the physical reproduction of labour power,

2. to training in techniques,

3. to training in social role or boss or worker,

we should realize that step 3 is down to him. It is not from Marx. Marx makes no assumption that workers need to be trained by schools to submit. He did not, for the very good reason that when he was writing it would have been blatantly counter factual.

If schooling is necessary for the training of workers in the correct behaviour – submission, following rules etc, how about the comparatively long period of capitalist industry that preceded the establishment of general education?

Capitalist industry ran for a good century in England before the 1880 Education Act introduced compulsory state schools. For most of the period, children went straight into factories without ever being educated. So whilst schools do now teach rules of good behaviour and attitude, they were not a precondition for this. At the other end of the spectrum consider transitions from socialist economies to capitalist ones. You had work-forces brought up in an education system in the USSR pre-1990 or in China pre-1980 that was non-capitalist, that did not exist to teach class subordination. But firms had very little difficulty in employing these people after the Soviet economy was privatized or once capitalist firms were re-allowed under Deng.

All that was needed to turn Soviet workers into capitalist wage labourers were the restoration of unemployment or in China the breaking of the ’iron rice bowl’. It is the absence of any other source of income, not ideological belief, that forces workers to subordinate themselves to employers. If the alternative is starvation you submit.

Turning to the bosses knowledge of ’how to speak to their workers’, would amount to nothing if they lacked the money capital to employ the workers. It is capital, not rhetoric that makes them employers.

So here is a first point where, no doubt inadvertently, Althusser starts to overemphasize the importance of an ideological apparatus, schools in this case.

Althusser then moves on and says that he intends to use the standpoint of reproduction to look at the base/superstructure division and the state. The Marxist tradition is, he says, strict when it says that:

The State is a ‘machine’ of repression which enables the ruling classes (in the nineteenth century the bourgeois class and the ‘class’ of big landowners) to ensure their domination over the working class, thus enabling the former to subject the latter to the process of surplus-value extortion (i.e. to capitalist exploitation).

Although he agrees with this formulation, he objects that it is not enough because it remains just a description of the state, not a theory of the state. So he goes on to give a short, but a more theoretical, account of the state. First, he distinguishes between state power, the thing that is fought over, and the state apparatus. The latter, he says, may survive revolutionary overthrows of state power.

To summarize the ‘Marxist theory of the State’ on this point, it can be said that the Marxist classics have always claimed that (1) the State is the repressive State apparatus, (2) State power and State apparatus must be distinguished, (3) the objective of the class struggle concerns State power, and in consequence the use of the State apparatus by the classes (or alliance of classes or of fractions of classes) holding State power as a function of their class objectives, and (4) the proletariat must seize State power in order to destroy the existing bourgeois State apparatus and, in a first phase, replace it with a quite different, proletarian, State apparatus, then in later phases set in motion a radical process, that of the destruction of the State (the end of State power, the end of every State apparatus).

He then says that in addition to the already recognised repressive machinery of the state there are what he calls state ideological apparatuses. This is Althusser’s significant innovation. Previous communists had not spoken of an ideological state machine. What was this machine made of then?

In his words the apparatuses are:

1. the religious ISA (the system of the different Churches),

2. the educational ISA (the system of the different public and private ‘Schools’),

3. the family ISA,

4. the legal ISA,

5. the political ISA (the political system, including the different Parties),

6. the trade union ISA,

7. the communications ISA (press, radio and television,etc.),

8. the cultural ISA (Literature, the Arts, sports, etc.).

What are we to make of this very diverse list?

Althusser quickly disposes of the objection that some of these are private institutions, saying that we have to look at how they function. Private institutions, as well as public ones, can reproduce ideology. That is fair enough, but what ideology?

If the initial claim is that the function of the ideological state machines is to reinforce the position of the employing class and ensure the production of surplus value, why are trades unions included? You could claim that some unions are company unions and don’t represent workers, but Althusser does not make this exception. Employers would far rather have no unions. Rather than encouraging subordination, unions encourage workers to act to limit exploitation. As they develop they often promote explicitly socialist demands. In what sense can these be ideological machines of the capitalists?

The same can be said of political parties. There are certainly lots of pro-capitalist parties that actively promote capitalist ideology. But not all. The RSDLP( Bolshevik) was a political party. Was it an ideological apparatus of the Russian capitalist state?

How can he justify such sweeping claims?

He does not bother to justify them or deign to qualify them.

I will leave these objections to one side. I agree that for several of these institutions the description Ideological State Apparatus is appropriate: press, religion, law etc.

2 Ideological state machines – feudal versus capitalist

Althusser goes on to distinguish the way the ISA functions from the Repressive State Apparatus(RSA).

“the (Repressive) State Apparatus functions massively and predominantly by repression, whereas the Ideological State Apparatuses function massively and predominantly by ideology.”

“the Ideological State Apparatuses are multiple, distinct, ‘relatively autonomous’ and capable of providing an objective field to contradictions which express, in forms which may be limited or extreme, the effects of the clashes between the capitalist class struggle and the proletarian class struggle, as well as their subordinate forms.”

“the unity of the different Ideological State Apparatuses is secured, usually in contradictory forms, by the ruling ideology, the ideology of the ruling class.”

The repressive state machinery, he says, functions to maintain, by force, the political conditions necessary for the reproduction of capitalist exploitation. By repression, the RSA secures the political conditions for the ISA to operate.

If we look back to the history of the Reformation, the political struggle over forms of worship struggles over the content of school textbooks etc, then we have to acknowledge that Althusser is onto something very important. Civil wars were fought over the wording of the Prayer Book in England and Scotland, Victors in war used their political power to dictate what was preached from pulpits across the country. So yes, politics does set the conditions within which the ISAs can operate. But these wars were at the very dawn of the capitalist age. The defining issue in Covenanting movement, the Disruption of 1843 or the 19th-century anti-clerical movement in France that Althusser refers to was the clash between bourgeois society and landlordism. It was between the rising capitalist economy and the old rural economy dominated by the descendants of the feudal ruling class. This point is important when we look at the function that Althusser attributes to the ideological state machinery: “it is the latter which largely secure the reproduction specifically of the relations of production, behind a ‘shield’ provided by the repressive State apparatus.”

Althusser would be right if he were just speaking historically about feudal or landlord economies.

In the feudal system, the peasants were openly and visibly exploited by having to either work on their lord’s land or to hand over a portion of the crop to the landlord. In the late stages of landlord domination, the farmers often became exploiters in their own right, employing waged labour on farms that they rented from landlords and paying over money rent each year.

Whatever the stage of development of landlord exploitation: labour rent, rent in kind or cash rent, it was a visibly unreciprocal transfer. In the earliest stages of feudalism, before the establishment of unitary royal authority, and when armed conflict between barons was rife, the exploitation could be disguised as reciprocity: protection in return for rent. But later it depended heavily on a church that preached:

The rich man in his castle,

The poor man at his gate,

God made them high and lowly,

And ordered their estate.

To challenge the dominance of the landlords you had to challenge the established church. The impetus for the conflict between laird and Free Kirk elder was the contradiction between free crofter and rent-seeking landowner. In the context of a capitalist market economy, the rights of the landowners were visibly in contradiction with the precepts arising from commodity exchange. The latter presupposed equal exchange, the voluntary exchange of commodities. Rent was not that. The pretence that the laird provided protection is long gone. It is fear of the factor, rather than the dread of raiding rival barons, enforcing collection.

If factor and constable are backed by the Kirk, let us break that Kirk.

Figure 4: The 1843 disruption of the Kirk was motivated by the conflict with the lairds.

Figure 5: Conflict between crofters and lairds in the late 19th century involved the naked use of force.

But Althusser is wrong when he projects this central role for ideology into the modern capitalist economy. One of the key lessons from Marx’s Capital is how capitalist exploitation comes about as a natural and direct result of relations of equality. Marx showed that the voluntary exchange of commodities at fair market prices led to exploitation.

No force or cheating is involved.

This sphere that we are deserting, within whose boundaries the sale and purchase of labour-power goes on, is in fact a very Eden of the innate rights of man. There alone rule Freedom, Equality, Property and Bentham. Freedom, because both buyer and seller of a commodity, say of labour-power, are constrained only by their own free will. They contract as free agents, and the agreement they come to, is but the form in which they give legal expression to their common will. Equality, because each enters into relation with the other, as with a simple owner of commodities, and they exchange equivalent for equivalent. Property, because each disposes only of what is his own. And Bentham, because each looks only to himself. The only force that brings them together and puts them in relation with each other, is the selfishness, the gain and the private interests of each. Each looks to himself only, and no one troubles himself about the rest.[8, chap. 6]

The capitalist relations of exploitation are not established by any ideologically sanctioned relations of domination and subordination. They reproduce themselves by the same means as any other commercial exchange, the mutual pursuit of self-interest. The end result, that shareholders accumulate wealth whilst workers have only enough to survive till the next payday is ensured by the very principles of freedom itself. All are free to dispose of what they have to sell as they wish, choosing the alternative that suits them. The alternative for one is either work or go hungry, and for another, it is investing in oil or property. This class difference can indeed give rise to political conflict, but at the economic level, the exploitation mechanism proceeds whether the worker believes in socialism or in free market economics. The central message of Marx’s Capital is that capitalist exploitation is an automatic result of the operation of the laws of the market.

But that is not the picture given by Althusser. According to him, it is the educational system that reproduces relations of exploitation:

no other ideological State apparatus has the obligatory (and not least, free) audience of the totality of the children in the capitalist social formation, eight hours a day for five or six days out of seven. But it is by an apprenticeship in a variety of know-how wrapped up in the massive inculcation of the ideology of the ruling class that the relations of production in a capitalist Social formation, i.e. the relations of exploited to exploiters and exploiters to exploited are largely reproduced.[3]

Given that society has advanced to the stage of machine industry, where the means of production are large and complex embodying the labour of many people for many years, self-sufficient production is just not a realistic option for the great majority. Industrial production means the dead labour of machines, ships and planes structures the work of the living. To work is to fit in slots created by the system. There is nothing more. A few can set up as self-employed and escape wage labour in niches as self-employed tradesmen or running small cafes etc, but for the majority this is impossible.

I am not denying that the education system propagates ideology, as do the papers and TV. But this ideology is relevant to politics, not economics. Because the economic relations of capitalism are self-reproducing, the only threat they face is the rise of socialist politics. Capitalism has been threatened by movements which aimed to take power and nationalise industry and commerce. Ideological struggles have been directed specifically at suppressing such socialist politics. The ideological apparatuses are not there, as Althusser asserts, to reproduce the relations of production. The ’business sector’ is quite capable of running that. They exist there to ensure that pro-capitalist parties hold political power.

To continue…

References

[1] Louis Althusser. Contradiction and overdetermination. For Marx, 114, 1969.

[2] Louis Althusser. Ideology and Ideological State Apparattuses. In Lenin and philosophy. New Left Books, 1971.

[3] Louis Althusser. Lenin and Philosophy. In Lenin and philosophy. New Left Books, 1971.

[4] Louis Althusser. On the reproduction of capitalism: Ideology and ideological state apparatuses. Verso Trade, 2014.

[5] Daniel Dennet. Consciousness Explained. Little Brown, Boston, 1991.

[6] Evald Vasilyevich Ilyenkov. The dialectics of the abstract and the concrete in Marx’s Capital. Aakar Books, 2008.

[7] Zedong Mao. On Contradiction. 1953.

[8] Karl Marx. Capital, volume 1. Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1954. Original English edition published in 1887.

[9] Alan Sinfield. Cultural materialism, othello and the politics of plausibility. 200

1 By way of contrast, Google gives 599 citations to the main work[6] of the Soviet philosopher Ilyenkov and over fourteen thousand to the main work[5] of the US materialist Dennet.

2 At more length in [4].